Hello again. This week I have a brief essay that I’m hoping will frame much of what will come later, starting with this question:

What is technology?

Easy enough, you might think: my computer is technology, and so is my phone. Most of my day is spent in front of one screen or another. Otherwise I’m using some older tech, like my car, to get from point A to point B.

And that’s all true. But perhaps we’re not being expansive enough. Let’s use a much more pedestrian example, and think about socks. Are socks technology? Well, what about the industrial machinery that manufactures most socks?1 ✅ How about the packing, shipping, and distribution systems through which you get your socks? ✅ But what if you get a hole2 in your sock and I darn it for you?❓

Now that things are getting complicated, I’m happy to introduce sci-fi legend Ursula K. Le Guin’s 2004 blog post, A Rant About “Technology.” Tired of being accused of not having tech in her science fiction novels, Le Guin makes, to me, an incredibly persuasive argument for a much broader definition of technology:

“Technology is the active human interface with the material world.”

We have been so desensitized by a hundred and fifty years of ceaselessly expanding technical prowess that we think nothing less complex and showy than a computer or a jet bomber deserves to be called "technology " at all. As if linen were the same thing as flax — as if paper, ink, wheels, knives, clocks, chairs, aspirin pills, were natural objects, born with us like our teeth and fingers -- as if steel saucepans with copper bottoms and fleece vests spun from recycled glass grew on trees, and we just picked them when they were ripe...

So for Le Guin, even though the two are often conflated, “hi-tech” is not synonymous with “technology.” “Simple” innovations, such as matches, can be extraordinarily complicated, essential, and worthy of consideration. Have you ever tried to light a fire without matches? I have, and it is no joke. Doing that stick thing is hard as hell, and you’re far less likely to have flint than matches.

Also, and I say this as a straight, white man: limiting our understanding of tech to engineering, science, and machinery precludes the people who have been excluded from those things by straight, white men throughout history. Just in the US, the legacy of BIPOC innovation is tremendous. There are also thousands of years worth of indigenous innovations, as well as a multitude of crafts and practices traditionally passed down from woman to woman, over centuries. For example, there’s the knitting, and eventually darning, of socks. Why limit ourselves? Le Guin writes:

Its technology is how a society copes with physical reality: how people get and keep and cook food, how they clothe themselves, what their power sources are (animal? human? water? wind? electricity? other?) what they build with and what they build, their medicine - and so on and on. Perhaps very ethereal people aren't interested in these mundane, bodily matters, but I'm fascinated by them, and I think most of my readers are too.

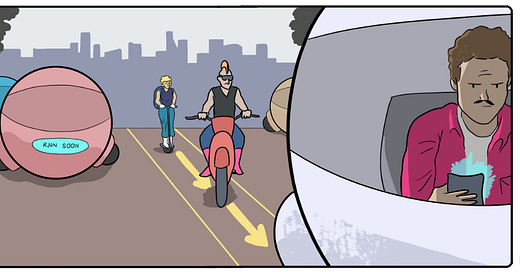

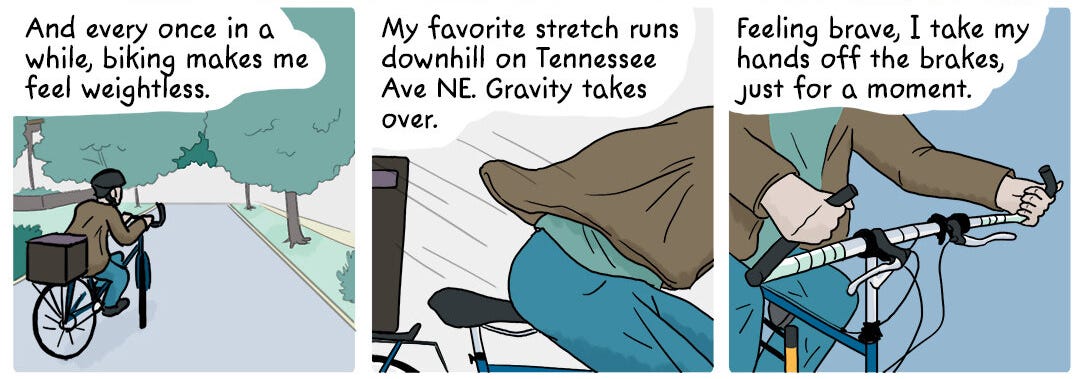

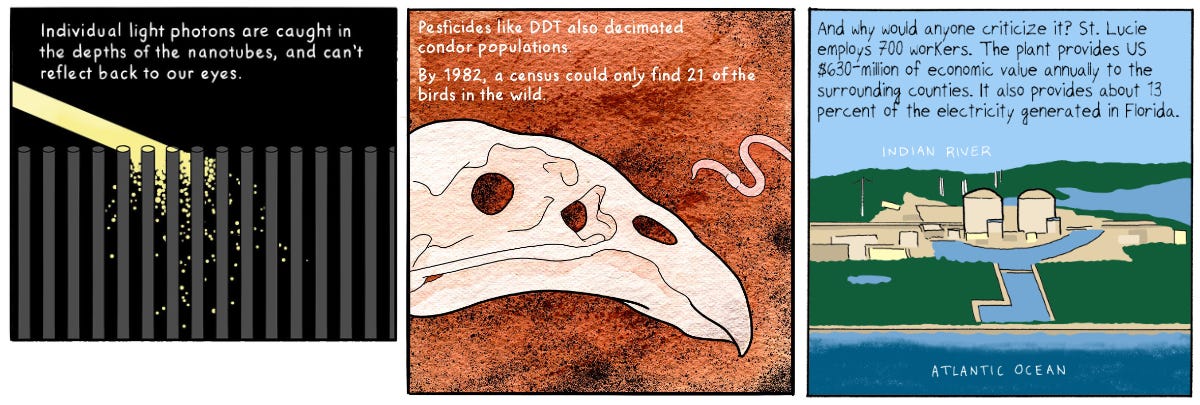

Sign me up. I realized recently that this concept is present throughout a lot of the work I’ve created so far (some pictured throughout this newsletter) as well as the pieces I’m excited to work on next. As I start sending out fiction, you’ll see a lot of different investigations of technology — some obvious, some less obvious. I don’t mean to compare myself to Le Guin, but I find her openness to be liberating. I invite you to roll this idea around in your head for a while and see how it feels.

To sum it up, here’s my mini manifesto about technology:

Technology is everywhere, and its development is not fixed or inevitable.3 To quote Le Guin, “Technology is the active human interface with the material world.” We all have agency, and we shape the technology we use, even when we don’t understand how it works. Tech is not the current sweeping us along downstream, it is literally the canoe that we use to navigate the river.

Unless all your socks are hand-knitted, in which case: congratulations.

Briefly, did you know that people have different patterns of wear based on their arches, etc.? My wife and I have different “sock hole signatures,” a term I just made up and am writing here so as to informally trademark the term.

This is another idea I feel so strongly about that I wrote a whole other piece about it recently.