In Pennsylvania for Thanksgiving, Alli and I were shopping for used books in a barn converted to that purpose. I stumbled upon something really interesting:1 a 1964 Dover collection of The Triumph of Maximillian I.

Stick with me here, because this is pretty unexpected and cool: Apparently, if you are the Holy Roman Emperor in 1512 (the empire consisting mostly of what we now know as “Germany” plus a bit more), and you want to cement your legacy, you might choose a popular mass media of the day — wood block printing. It’s more economical and longer lasting than a real Roman-style triumph parade, but still has serious propaganda potential.

Taken together, the 1392 prints HRE Max commissioned stretched to some 177 feet, and were meant to be either pasted on the walls of civic spaces and palaces, or bound up as a book. The Emperor himself supposedly dictated the descriptions of each print, as well as the poem text to accompany it — the comics script, basically. Masters of the form, including Hans Burgkmair (who worked a prominent “HB” into most of his drawings) and Albrecht Dürer3 executed the drawings in shockingly ornate detail that still compels viewers over half a millennia later.

Wood block printing, both here and in places like Japan and Mexico4, is such a fascinating medium: both vital and powerful imagery, but also cheap and mass-produced, which in many cases has allowed works to survive until today and thrive in the public domain.

In reading through the Triumph, I was struck by how deliberate the political messaging is. It really hammers home the Emperor’s supposed Roman lineage by having nearly everyone (except prisoners) wearing laurel wreathes. Many illustrations brag about his accomplishments, both large and small, from military conquests to innovations in the sport of falconry that allowed it to go year-round.

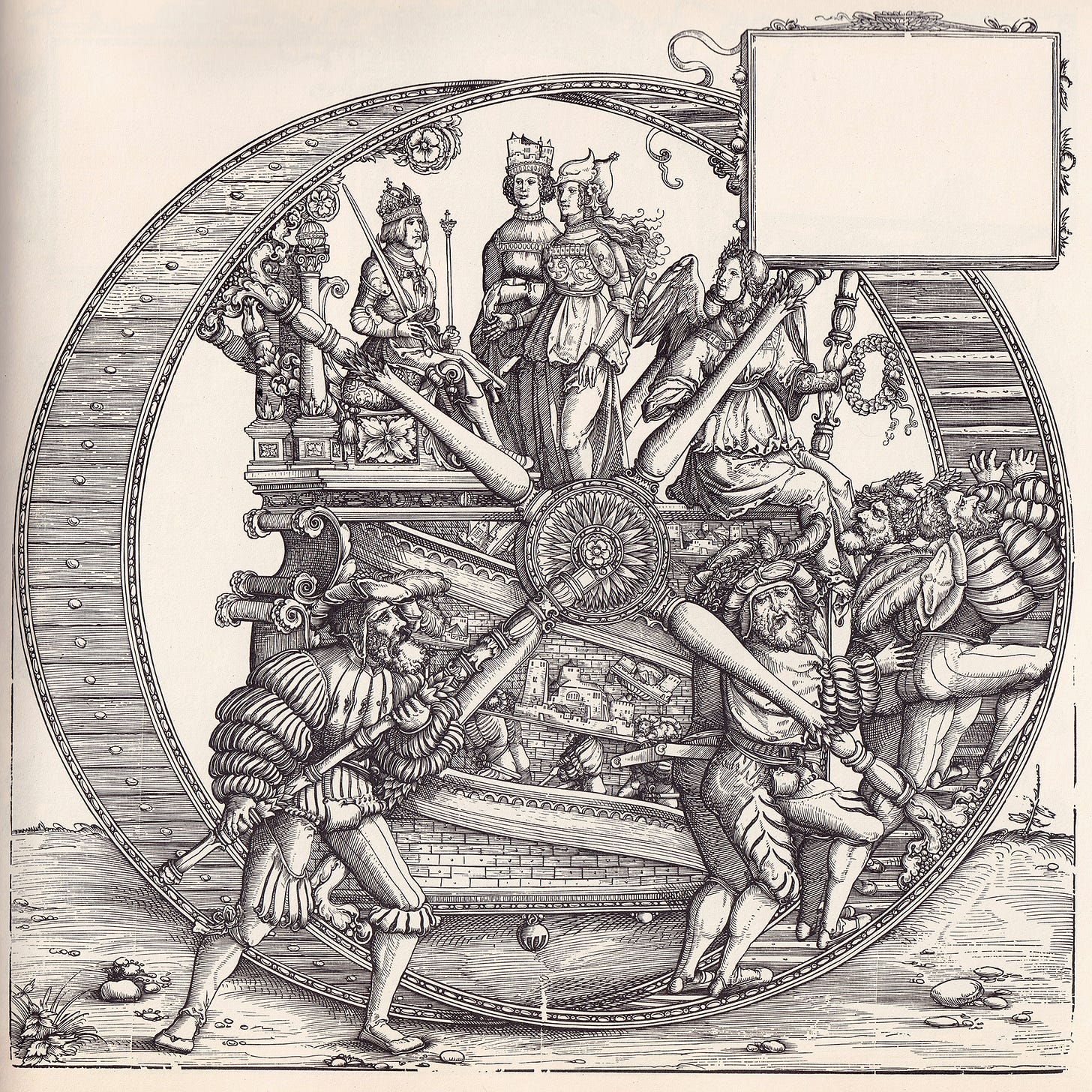

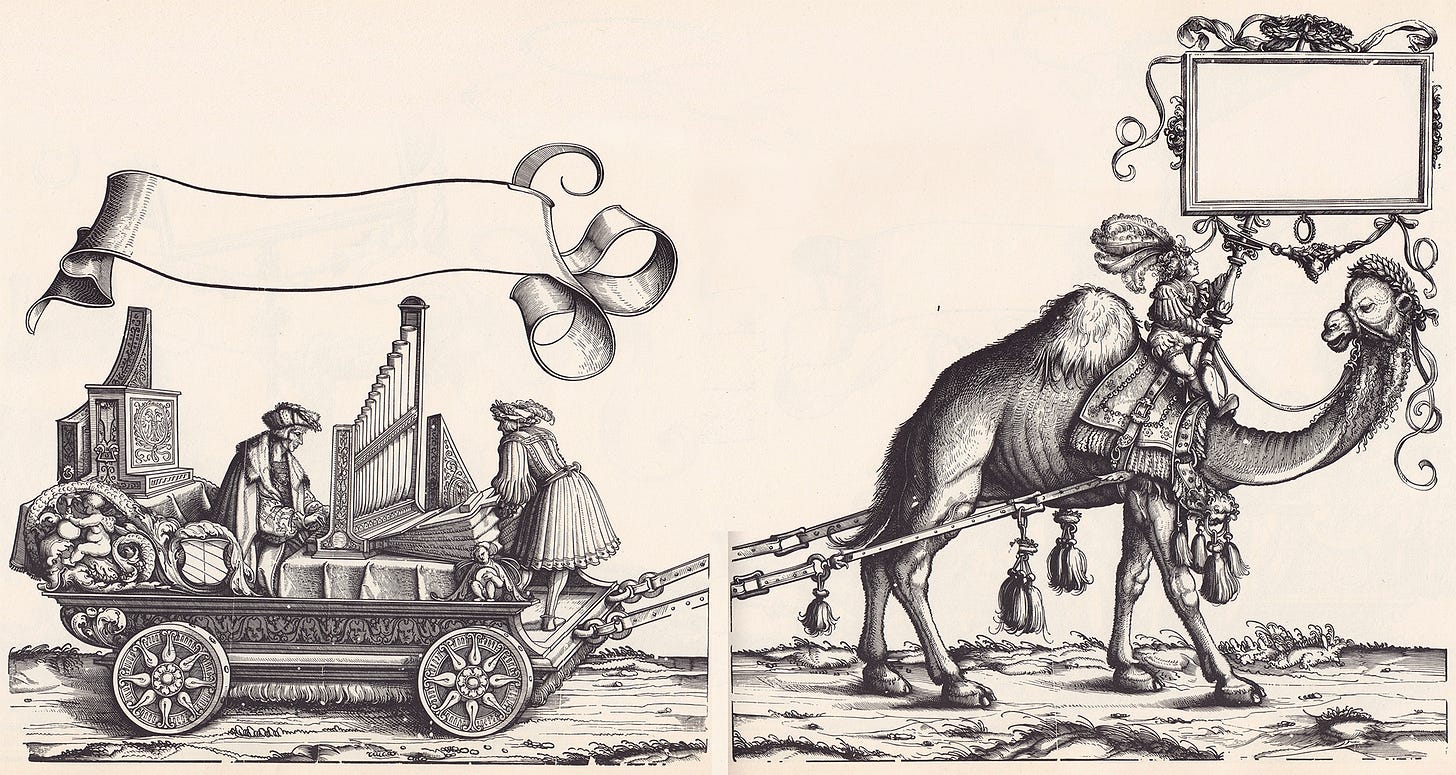

The Triumph is not exactly a realistic portrayal of a parade. You get a lot of truly nutso juxtapositions like the one below, of a camel pulling a pipe organ cart, and a lot of imagined animals. There are also multiple scenes with the Emperor himself and entire cities rendered in cart form. Many of the knights have diagrammatic armor, showing how a particular piece is meant to explode upon a direct hit.

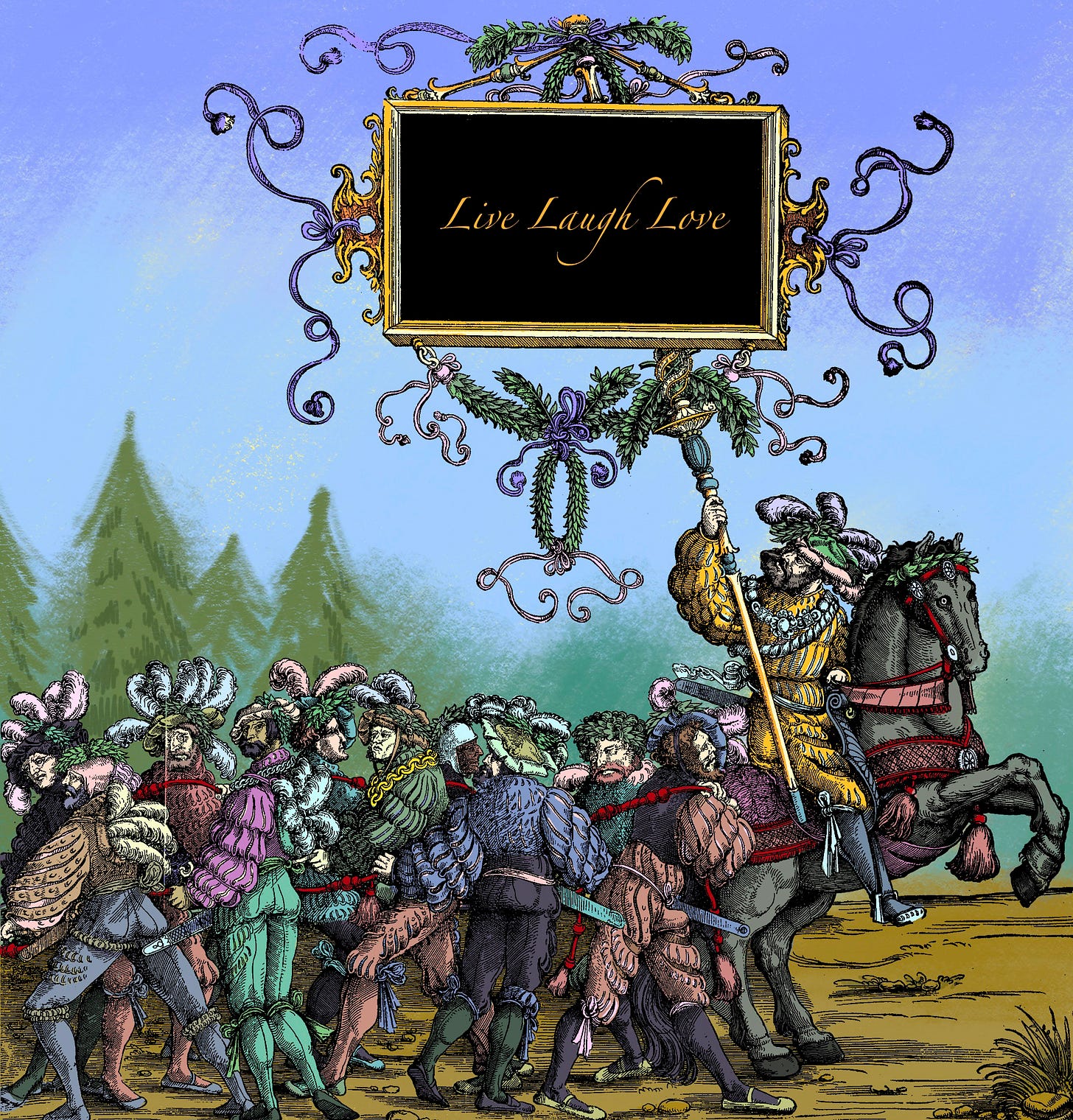

To engage with this more directly, I reduced a page to black and white line art and practiced coloring techniques on it in the iPad art app Procreate. I think the results, below, are mixed, but I noticed a lot in the process:

The detail is amazing. I love Wolf Hall5, and I thought I had some idea of what Mantel meant by “slashed doublets,” but these are super clear and and so intricate. Also, the artists are so good at varying the people and costuming, and turning the occasional human or animal face directly out at the viewer.

I chose this image because of the emphasis on the sign, but after hours with it, it occurred to me that these men are pulling on something. What are they pulling? I looked it up, and here’s how Maximillian described this spread, images number 103 and 104:

After these wars depict a trophy car with all sorts of Netherlandish and French weapons and banners of all colors, also all sorts of armor (with a man on horseback before).

Here’s the trophy car they’re carrying:

Damn! I can’t even imagine how long this took to draw. In fact, the Triumph wasn’t actually finished until after Emperor Maximillian I died. But that is, in fact, the point. This work was meant to survive him and proclaim his greatness. And now, as part of the public domain, I think these fancy drawings of blank signs could be repurposed quite nicely for all sorts of things, from invitations to cards to ornate memes. That’s the thing about legacy: it’s out of your hands.

One emperor’s propaganda can become a modern cartoonist’s silly experiment and newsletter — a window back through the ages.

That we know of!

Dürer was minimally involved in this one, but drew most of the Triumphal Arch and Carriage.

HRE Max actually fought alongside a young Henry VIII in the Battle of the Spurs