Hi from Tioman Island, Malaysia. 🇲🇾

In this newsletter I have two essays: one that is a bit difficult and then something else a bit lighter and more pleasant to balance it out.

What our country did

America shares something in common with almost all1 of the nations of Southeast Asia: we were colonies that sought (and often fought for) independence from a European ruler. We2 should, logically, have had common cause with these colonies, as they looked to follow in our example in the mid-twentieth century.

However, our actual treatment of these countries, beginning in the years after the second World War, was often so horrendous it makes me queasy to write about now, all these years later.

If, like me, you know vaguely that our country was responsible for “some bad shit” in foreign countries, but struggle with the details and the totality of those actions, I heartily recommend The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade & The Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World, by Vincent Bevins. Yes, this is that kind of essay.

As you may know, during the Cold War our country not only dropped a lot of bombs (“The United States dropped three times the tonnage on Cambodia that fell on Japan during World War II, atom bombs included,” writes Bevins), assassinated a lot of democratically-elected leaders, and spread a lot of propaganda. Our country was also what Bevins calls an “expansionist and aggressive power” that facilitated a lot of truly awful violence.

Sometimes that violence came in the form of lists of people our country wanted dead, and other times it was spread using techniques that our government trained foreign military generals to use against their own citizens. Here’s Bevins:

This was a new characteristic of the mass violence. People weren’t killed in the streets, making it very clear to families that they were gone. They weren’t officially executed. They were arrested and then disappeared in the middle of the night. Loved ones often had no idea if their relatives were still alive, making them even more paralyzed with fear.

Look, despite appearances, I’m not here to lecture. Like me, you probably knew about some of this stuff, but I was just floored by the enormity of this campaign, including in places like Indonesia, where very few Americans know what our country helped accomplish. Over six months beginning in October 1965, somewhere between 200,000 and one million Indonesians were killed because they were suspected Communists, or just because someone had a score to settle and could get away with it. And thanks to Bevins, I now know just how much our country pushed for, and benefitted from, all that slaughter of non-white people a world away.3

Bevins is an American foreign correspondent, and he does a great job layering in the personal stories of real people while telling the maddening, decades-spanning story of the Cold War. For Bevins, the moral is not that we eventually beat the Commies because we had the better system. Instead, writes Bevins, “we can see the Cold War as the global circumstances under which the vast majority of the world’s countries moved from direct colonial rule to something else, to a new place in a new global system.”4

I really recommend this book. But I know, realistically, that most of you are not going to read it, so I’ll leave you with this:

In the years 1945-1990, a loose network of US-based anticommunist extermination programs emerged around the world, and they carried out mass murder in at least twenty-two countries (see Appendix Five). There was no central plan, no master control room where the whole thing was orchestrated, but I think that the extermination programs in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, East Timor, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Iraq, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, the Philippines, South Korea, Sundan, Taiwan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Vietnam should be seen as interconnected, and a crucial part of the US victory in the Cold War. (I am not including direct military engagements or even innocent people killed by “collateral damage” in war.)

Traveling with the Master

Phew! OK. Still with me? Let’s talk about something else.

Recently, we spent a week in Singapore. It was both invigorating and exhausting to be in a vibrant city again, and we had our fill of both expedient, convenient urban transit, and amazing Asian food for very little money.

At National Gallery Singapore, we took in an exhibit of Chinese painter Wu Guanzhong, who I had never heard of before. Wu has a fascinating biography, spanning from his education and travels in Europe, through his personally devastating experiences during the Cultural Revolution,5 and finally to a period of international fame. Similarly, his body of work as a painter evolved considerably, and that’s what’s most interesting to me. To explain, let me start with two paintings by other artists from elsewhere in the museum.

Here’s how another painter, Basoeki Abdullah, painted the undated “Sunset.” It’s a quite pretty, if conventional, oil painting of a rice paddy.

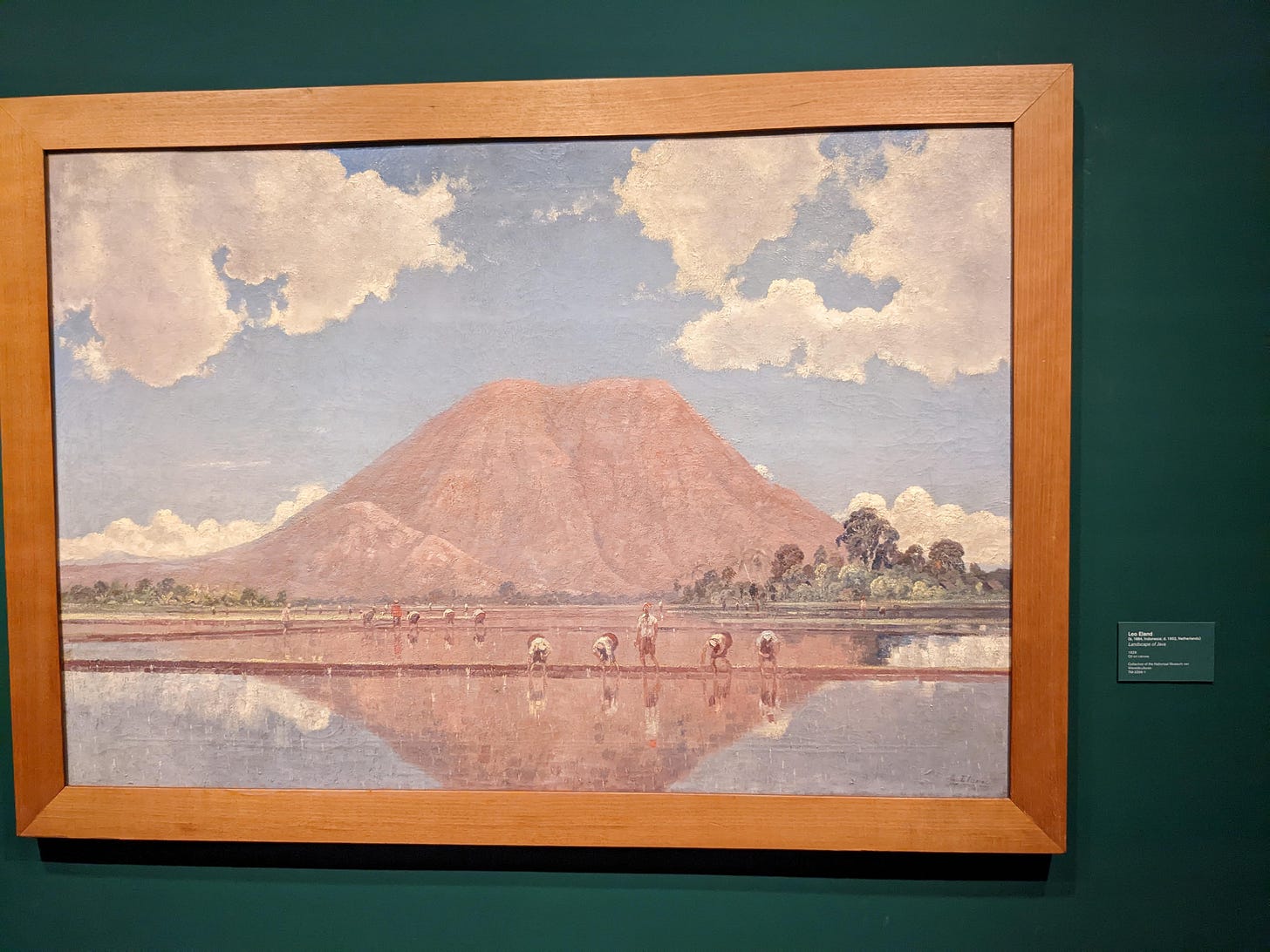

And here’s Leo Eland’s 1929 “Landscape of Java,” which playfully uses the glass-like surface of the paddies and also brings in human figures and mountains.

Here are two works side by side. Both are by Wu. On the left, is a painting of rice paddies from 1973. As you can see, it’s a competent, subtle, realistic rendering of the subject, not too dissimilar from the above paintings. On the right, this is also rice paddies, but from 2006. Thirty years later, Wu worked primarily in Chinese ink and color ink on paper. Quite a shift, no?

I’m struck by this transformation, and how Wu was able to so deftly blend his Western-style landscape work with nearly abstract, calligraphic brush work.

I’m thrilled to have learned about Wu, who died in 2010, and have my eyes opened by his work. He had a cartoonist’s sense of clarity and concision, which is one of the best compliments I know how to give an artist.

Speaking of toons, I’ll end with this: if you’re in the DMV, or within driving distance, I would seriously consider attending the Small Press Expo in Maryland this weekend. Showering independent artists with cash in exchange for lovingly reproduced copies of their hand-drawn work is the best feeling. This is the first time the show is happening in person since 2019, and it seems like there is a ton of pent-up enthusiasm and energy. Please let me know if you go and what you bring home in your haul. I’ll be incredibly jealous of those of you who can go!

–Josh

P.s. Thanks for reading the FREE RIDER prologue recently. There’s a lot more to send you, and I’ll probably do it like that, by sending a few emails in a row.

Except for Thailand

Because most of the people who read this are likely to be American, I’m going to speaking about the United States as “our country.” My apologies if this does not apply to you.

I’m not interested in arguing the merits about whether, even if someone was a Communist, that’s a justifiable reason to execute them without trial. If that happens to be your opinion, I strongly encourage you to read this book.

Here’s another metaphor for understanding the two phases of the West acting on SE Asia: First there’s the extractive forces of colonialism that, from about 1500-1800 took things like fish sauce and sambal, and turned them into something like worcestershire sauce, and eventually, ketchup. Then there’s anticommunist globalism, that starting after 1945, brought us Western tourists back to these countries, along with ketchup for our fish and chips.

Oh, what’s this? Maybe there are some common threads between these two parts 😉

Thanks for the anti-communism essay Josh -- I had no idea of the scale of killing in Indonesia in particular. Hope the trip is going great -- we miss you at New_ Public :-)