So let me tell you about earlier this week, when I was on a tour of Mayan ruins. (Surprise, Alli and I are in Mexico. It has been great working from Mérida.)

It’s hot, but pleasant in the shade, and it’s not very crowded. There are iguanas everywhere — basking on top of stone temples and poking out between limestone blocks1 that were cut without metal tools and stacked by hand over a thousand years ago. Pepe is a great tour guide. He’s doing a great job of explaining the archeology, with plenty of nuance, and an appreciation for how we have come to know what we know about Mayan life.

The temples and ruins at Uxmal (the x is pronounced with a quick “sh”), an UNESCO World Heritage Site, are fantastic to walk through. And then Pepe starts saying something his daughter, an architecture student, told him about Frank Lloyd Wright. Wait a second… I know this one.

Wright was inspired by the Mayans, who lived throughout Central America, in what are now five different countries. In college, I briefly visited Guatemala, home to the Kʼicheʼ, a completely different indigenous group descended from Mayans, over a thousand kilometers away.

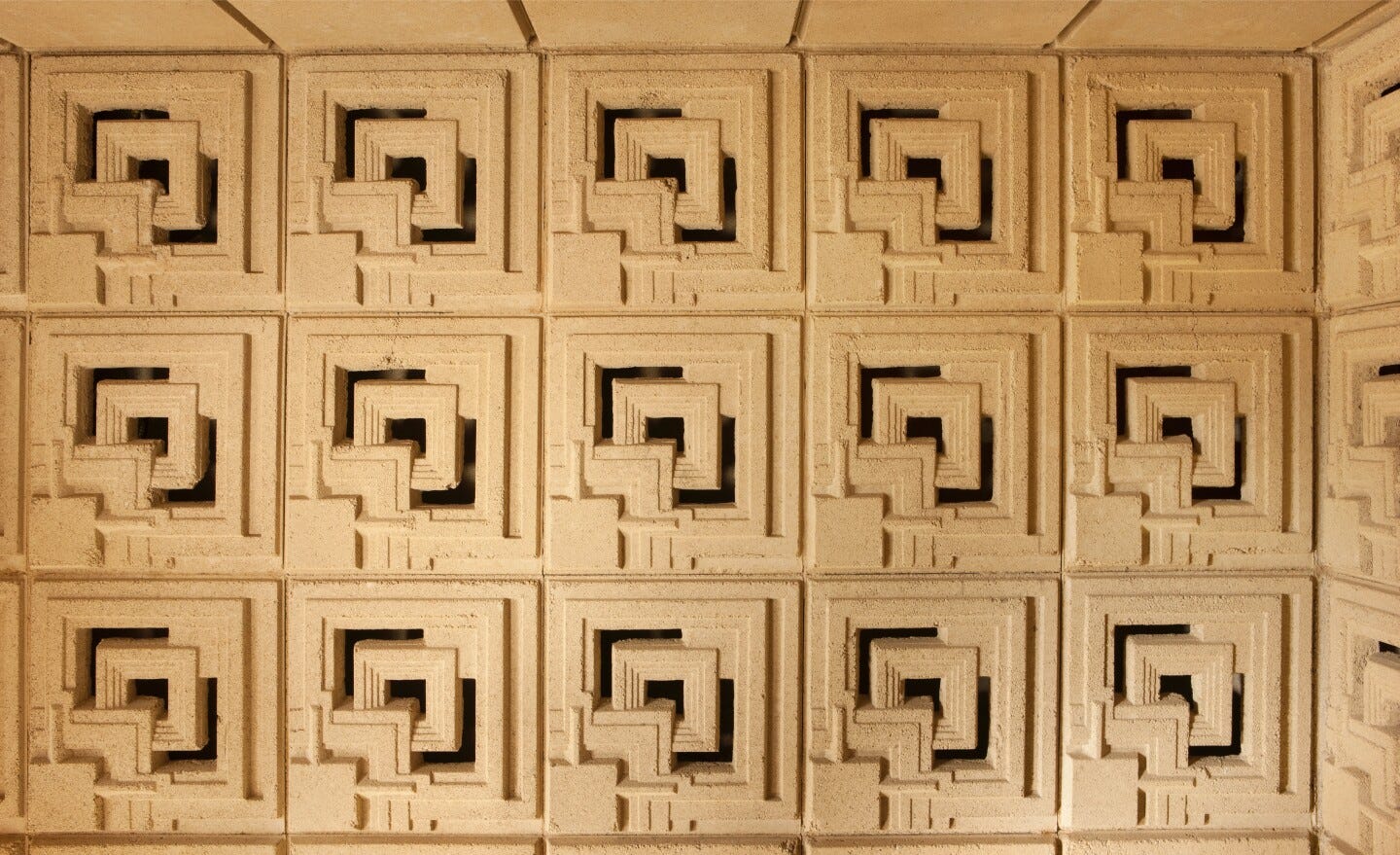

But Wright wasn’t just inspired by any Mayan architecture, he was fixated specifically on one variation: Puuc style architecture from the Yucatán peninsula. And precisely, this building at Uxmal, referred to as the Governor’s Palace.

It all came flooding back to me in an instant: I wrote an article about this! Well, kind of. In 2017 I wrote about how Frank Lloyd Wright built several Mayan-influenced concrete block houses in Los Angeles. The last, the Ennis House, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

It went on to have a unique legacy in film and television, appearing in or inspiring locations for Buffy, Twin Peaks, Blade Runner, Game of Thrones and many others:

Mayans and other pre-Columbian societies built intricately carved stone structures and enormous, stepped-back pyramids. They also had a rich ornamentation featuring jungle animals and gods. In the 1920s, as Art Deco began to take off, copying Mayan designs was becoming popular with American architects. Wright wanted to incorporate some of those elements in a way that would emphasize LA’s topography and climate, and that was affordable and replicable throughout the region.

I remember a lot about the process of writing this one, only five years ago. I was so excited to jump back into freelancing after my journalism fellowship at the University of Michigan, where I had taken a great “Understanding Architecture” class. Earlier in the summer, I had a blast working on a piece about the buildings in Steven Universe. The message from my editor was clear: feel free to keep pitching us stories about pop culture and architecture. And so now I was now working on my second written piece for The Atlantic, a fantastic publication I interned for back in college, and later did some comics for.2 I really poured myself into it, even going to the Library of Congress to request some Wright-related documents.

There was so much to write about, and I distinctly remember doing a lot of research into Art Deco LA’s fascination with Mayan ornamentation, and realizing that very little of it actually made sense to put in the finished piece. Here’s a paragraph from the first draft that doesn’t appear at all in the published version:

In his autobiography, Wright claims he had a book as a child where he learned about the Maya. “That may be spinning a myth,” says Kenneth Breisch, architecture professor at the University of Southern California and responsible for the restoration of the Freeman House, another Wright textile block home in LA. According to Breisch, it’s just as plausible that he was introduced to them through an exhibit at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. “I’m almost sure he was introduced, or reintroduced to the idea there.” Either way, Mayan influence started to dominate Wright’s LA projects.

It’s fascinating to think about how FLW, a very white American born in the mid-19th century, who wore a cape and carried a cane, came to incorporate this Mayan temple into his “organic architecture.” And it’s even more interesting to think about how Wright’s Ennis house — sometimes the interiors and sometimes the exterior — defied genre and era to represent many different locations on screen:

The geometric patterns on the textile blocks could be seen as Central American, or as reminiscent of circuitry. The blocks look both earth-wrought and machine-made, which they are. Through its specificity, the Ennis House has acted as a pop-cultural cipher: It blends into the multiracial future depicted in Blade Runner and as a lair for the undead in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

At Uxmal, you can draw a straight line from the central door of the Governor’s Palace to the Platform of the Jaguars, and five kilometers past that to the pyramid at Cehtzuc, and about every eight years, to Venus, visible in the night sky. But you can also draw a line, through space and time, from the construction of this temple around 900 CE in the Yucatán peninsula, to Roaring Twenties Hollywood, to film sets ever since at least the 1980s. It’s fun to think about, or at least it is to me.3

Since I wrote the piece, the Ennis House sold for $18 million in 2019, to the folks who started Lord Jones, the CBD brand. Why not? They can certainly do whatever they want with it, but I hope they open it to tours in some capacity. One day I’ve got to close the loop and see the Ennis House for myself.

I’m not sure how this piece will find you. When I started writing it, Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine yet, and now they have, and the situation is getting sadder and more serious. Still, I hope that you’re well, and this has given you something else to think about for a few minutes. I’ll have more to write about our trip soon. Getting outside of the country for the first time in two years has been really, really great.

– Josh

How many do you see in this photo? Can you find all four??

Sometimes I like to throw in this anecdote: my class of interns wasn’t paid, but then my friend Bobby called them out for this (I can’t remember if he wrote the article or was just quoted in it), and they reversed the policy, retroactively paying me thousands of dollars when I was in art school. Thanks Bobby!

Another great, unrelated example of drawing a line like this is the one between generations of Calders in Philadelphia.